The Millennium approaches...

Prince's apocalyptic party anthem, '1999', had really set the scene by the time the year it referenced rolled around. Clubland had been rehearsing for these days of judgment since the 80s, trading every weekend in the currency of anticipation. The lyrics, delivered passionately by the dear departed musical maestro over a classic guitar riff and crashing cymbals, were spookily prescient: people running everywhere under a purple sky could describe any one of a number of rave episodes. Minds attuned to popular and counterculture raced as the dreams of the manically creative sprang to life in the dawn light.

Europe lent its name and credibility to the euro, which was established on 1 January. Costly conflagrations simmered out east while in the west of the continent borders dissolved. The internet was slow and unreliable and was yet to live up to the hype.

In the US, a scandal-ridden President Bill Clinton, a slave to his dark desires, heaved a huge sigh of relief upon his acquittal in impeachment proceedings. However fellow members of the wired generation were less sanguine: thoughts turned to the ‘Millennium bug', a potentially devastating flaw in the programming of computerised systems already essential to everyday existence.

Manchester DJ, Griff, so famously versatile that like a popstar or Brazilian footballer he only needed one name, recalled the panic over tech-reliant machinery which might grind to a halt or maybe even fall from the sky.

“There was a lot of excitement coming up to the millennium,” recalled the man who ruled the main room at the (then) World's Biggest Club, Privilege, playing for 10,000 punters every Monday at the legendary Manumission. “There was a lot of uncertainty as well because everybody had that fear that with Y2K everything was going to stop.”

Clearly this would have been a disaster for Prince, Griff and those others carving a career in creative industries in thrall to synthetic rhythms emitted by machines. The bulky boxes of plastic and metal were beloved but not networked in the modern sense. Analog systems remained an essential part of the process with every club gig reliant on a manufacturing process to etch data onto vinyl, inserted into sleeves then quaintly distributed by hand and motor vehicle.

Caressed with a diamond-tipped needle, those discs of black gold changed lives. Energetic, receptive and positioned advantageously in front of massive speaker stacks, the club-going public were rendered transcendent as the century spun to its dizzying conclusion.

“Probably the biggest tune I felt was Armand van Helden's ‘U Don't Know Me',” Griff told Spotlight. The number one smash in the UK, featuring the stellar vocals of Duane Harden, was “a killer track”. Casualties included Duane's career, a reminder perhaps of the ephemeral nature of success in the intense leisure industry.

But like van Helden, Michael Griffiths has endured, although he does acknowledge that in the wake of Brexit “it's a really kind of turbulent time”.

“It's a kind of funny one for me because I work in Spain, my missus is Austrian, our kids are Austrian-English but they've not been to the UK so to exclude yourself from that is a difficult one. I guess I understand people's reason for doing that but I don't think it's something I would've thought was a great idea to kind of distance yourself from the main landmass that's closest to ya. In favour of what? Closer trade ties with America? Well, that seems to have gone a bit weird.”

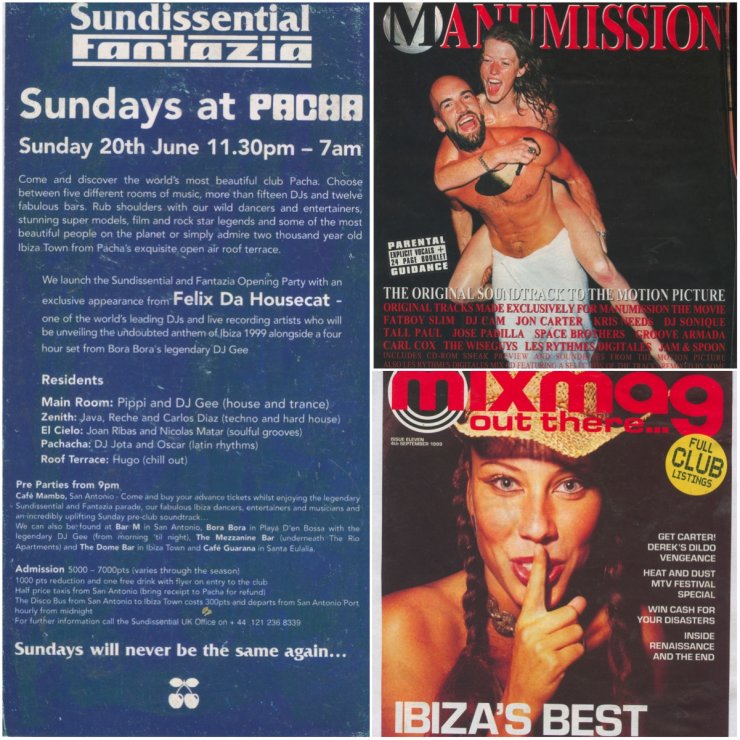

Manumission in full swing

The father-of-two now runs Mallorca Rocks, the upstart offshoot of Andy and Dawn McKay's wildly successful Ibiza Rocks. Rocking though was one thing 1999 did not do. Indie's wetness was typified by 'Why Does It Always Rain on Me?', the unambitious tune that came from Scottish foursome Travis. Boomtown crowds sought a different buzz and were lured in their millions to spectacular cathedrals of light and sound just a two-hour plane ride away from Europe's hubs. “We were pulling in so many people,” Griff says wistfully. We asked the now father-of-two if he knew upon hearing a tune for the first time it would work in a really big room.

“Yeah, I used to get that all the time at Manumission,” he says with understandable enthusiasm. “I'd always be excited to play the next tune if it was like that, because you'd hear it and you're gonna go ‘I know what reaction I'm gonna get.' You get those endorphins released in yourself because the reaction from the crowd was incredible. It would be just one movement in unison by thousands and thousands of people. And it wasn't about thinking it was great I'm doing this, it was like, ‘this is going to be such a good reaction for everybody, and everybody is going to go mad…' There were times when you'd listen to it and you'd go ‘this is going to kill it, absolutely make people lose their minds.' That was the best feeling.”

Arguably a golden age of rave, the year was endowed with classics somehow undiminished by insanity-inducing repetition. Indeed their ubiquity only added to the effect. “Phats and Small, ‘Turn Around', that was a big tune,” Griff reminisces, now on a roll. “Darude [‘Sandstorm'] was 1999. That was a tune. I think that probably got dropped. Because that was the time when that kind of music was kind of trance but it was alright, it wasn't really embarrassing trance.”

Other works of aural art achieved apotheosis in the oversized and under-plumbed San Rafael venue: The Chemical Brothers stripped the genre back to crucial elements like bass, drums and hero worship with ‘Hey Boy Hey Girl', while fellow superstar DJ Fatboy Slim harnessed the tornado-like zeitgeist with ‘Right Here Right Now'.

“That's a very Manumission moment right there,” says Griff of the iconic track created by the Manumission regular.

A golden age

Manumission, a powerful term denoting freedom from slavery, was the word of 1999. The previous year the British brand exploded into the global consciousness via BBC Radio 1, tabloid outrage and the gushing word of mouth recommendation. By June ‘99 it was attached to everything from magazine covers to a movie, a motel, money, even people's names.

Mike Manumission, in partnership with his brother - the aforementioned Andy McKay - and his missus Claire, was at the centre of this maelstrom. He and Claire had really gone the extra mile on promotion. “They just spread the love,” says Griff. The pair, who shared a very intimate part of their lives with the public, belonged to that public. The excessively accessible celebrities leapt over the velvet rope to party in the pit and surrounded themselves with the wild and the artistic. As a PR strategy it was extremely successful. In terms of lifestyle they might have been on a different planet but they seemed to know everybody in their island universe. Their Privilege party was a behemoth, but nowhere was the madness more concentrated than at the Manumission Motel, on the dusty outskirts of Jesús.

“It was just berserk,” recalls Griff. “The VIP culture was there but it wasn't how it is now… you wouldn't be surprised by who you saw. And you wouldn't feel out of place. So the fit girl that passed you on the steps, you looked back and it was Kate Moss and then you thought, who's the small geezer with the mullet? Oh, that's Maradona. You weren't surprised. It was just normal and everybody mixed. It's one of those feelings you don't often get I think, where you feel like ‘this is the place in the universe that is one of the most important places right now.' Even though it might not have been in your head you felt at the epicentre of everything that's going on in this kind of world.'

He goes on to describe what it was like working with Andy and Dawn McKay. “As employers, they were brilliant, fantastic. I don't think I've had a single disagreement in all my time I've worked with Andy. He's always a very calm person and I've never seen him lose his temper. He's methodical and he thinks through things. He just makes the right decisions and and has good ideas that other people don't have that he acts on, and it's the same with Dawn. She's got a great creative edge and saw the gap in the merchandising market when nobody else was really there."

And was it the same with Mike and Claire? “Haha. Well, it was a funny time to be working because there was a lot of everything going round. It was the year of the Motel so you know that was just berserk, ‘98, ‘99. Jesus, the Motel had a feeling. I don't subscribe to these things often, but the Motel was a feeling. After two days of being there it was like ‘get me out of here, I have to get out.' Because it was enveloping you. I think they were caught up in a kind of craziness and you know, they just spread the love. That's what they did, they just spread the love, I guess that's the best way of describing it... they wanted people to do well, they were interested in people's ideas. They'd take it on board. Here's a story, this sums up how it was: there was a couple that used to come into the office to get paid, for two years, and until somebody went ‘what do they do?' And the answer was ‘Oh they work for so'n'so', it went round. They didn't actually work us, they just came in and got paid and nobody had questioned it. Because we were pulling in so many people and the money was there, we didn't really notice and everything was possible. Every crazy idea. There was no handbrake, it was like. And that's why it was how it was. Because if you sat down and analysed it and looked at the numbers you'd go ‘that's not gonna work' but that wasn't the point.

So, looking back, if you could tell your ‘99 self something, what would it be? “It would probably be ‘shave all your hair off now, a year before you actually did, and probably look at buying something in Ibiza, because it would only be a good investment.'

The times they are a-changing

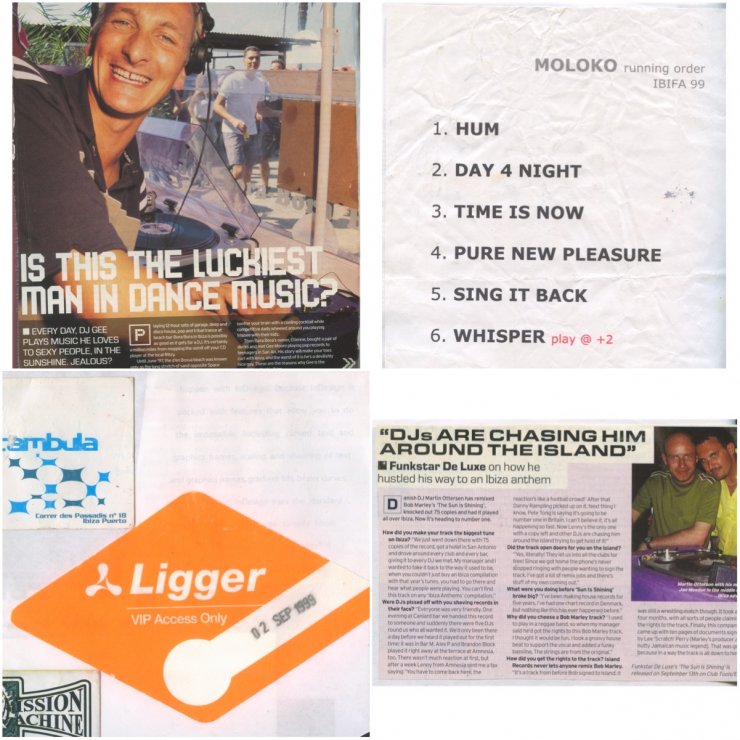

Of course Manumission's after party was Carry On at Space, also going through its own purple patch. Partying in the sunshine lifted the already ebullient mood. Hierbas was downed, silliness abounded. Incredibly the merry band had enough energy to stagger across the road to dance on tables and kickstart another institution on the sand at the beach bar / free club Bora Bora, soundtracked by the irrepressible DJ Gee. On Sundays, again all roads led to Playa d'en Bossa for Home, Darren Hughes' epic day'n'nighter, which featured the world's biggest club-focused artists from the more credible end of the spectrum. A notable highlight in a contested space was Sasha and John Digweed's seven-hour back-to-back set one Monday morning. At its conclusion many of those honoured to attend were literally crying with emotion.

From that resort's sandy beach, Ibiza Town could be seen shining like a jewel. At the summit of Dalt Vila the cathedral looked down upon a maze of narrow, cobbled streets lined with bars, restaurants and shops and buzzing with outrageous parades, tourists, locals and seasonal workers having the times of their lives. Just a ferry ride away across the harbour was the petite El Divino, a favourite with the glamorous occupants of the superyachts and luxury launches moored close by. Neighbour Pacha stood strong and proud, especially on Friday nights with Ministry of Sound, a testament to the drive and creativity of the Urgell family who got the whole disco ball rolling. But standing on the terrace sipping an eye-wateringly potent vodka limón it was possible to detect the distinct whiff of overexploitation.

“It was the time when DJ fees were just getting talked about as being really exorbitant and seemed to be like it was unsustainable, but little did we know that was just the tip of the iceberg,” says Griff.

After a bitter-sweet series of closing parties studded with September storms, plans were hatched to reconvene for December 31, the last day of the 90s…

Top 5 tracks from 1999

'U Don't Know Me', Armand van Helden

'Turn Around', Phats and Small

'Hey Boy Hey Girl', Chemical Brothers

'Right Here Right Now', Fatboy Slim

'Sing It Back', Moloko

WORDS & PHOTOS | Dr Mick